Quote of the week

Quote of the week from the Analects

Since the early thirteenth century, ‘grief’ in the English language has referred to “suffering, pain, or bodily affliction,” coming from grever “afflict, burden, oppress” and the Latin gravare, “make heavy” or gravis, meaning “weighty”. In its modern context, grief is perhaps best understood as mental pain or sorrow for the death of a loved one, which is mostly a reactive expression to the immediate feeling of loss. Crying and feeling shocked and sad at a loss is an example of grief being carried out. Mourning, on the other hand, which comes from the Old English murning, means to long after or remember sorrowfully. It is a state where one mushc formalize the emotion of grief and begin to construct a post-death vocabulary for the loved one and recover from the feeling of disjunction. It is about accepting the reality with the loss and creating some stability in one’s emotive life after suffering from the initial shock and sadness.

In Confucianism, grief and mourning are considered natural and necessary parts of living out a humane life. Grief demonstrates a commitment to the loved one that passed away and to carry out grief appropriately serves three functions. The first is to honor the person that passed away. For example, Confucius suggested a three-year mourning period following the death of one’s parents. If one truly honored and cared about the loss, then the usual joys of life would no longer bring joy and ease but instead only increase anxiety and feelings of loss. The second function of grief and mourning is to remember one’s ancestors. There is a duty to reflect on one’s past and the death of a family member should cause one to both grieve and commit to carrying out their ancestors memories by continuing traditions and rituals. Finally, grieving properly allows one to move into the stage of mourning and adjust one’s sense of reality to no longer having the loved one around.

Quote of the week from the Zhuangzi

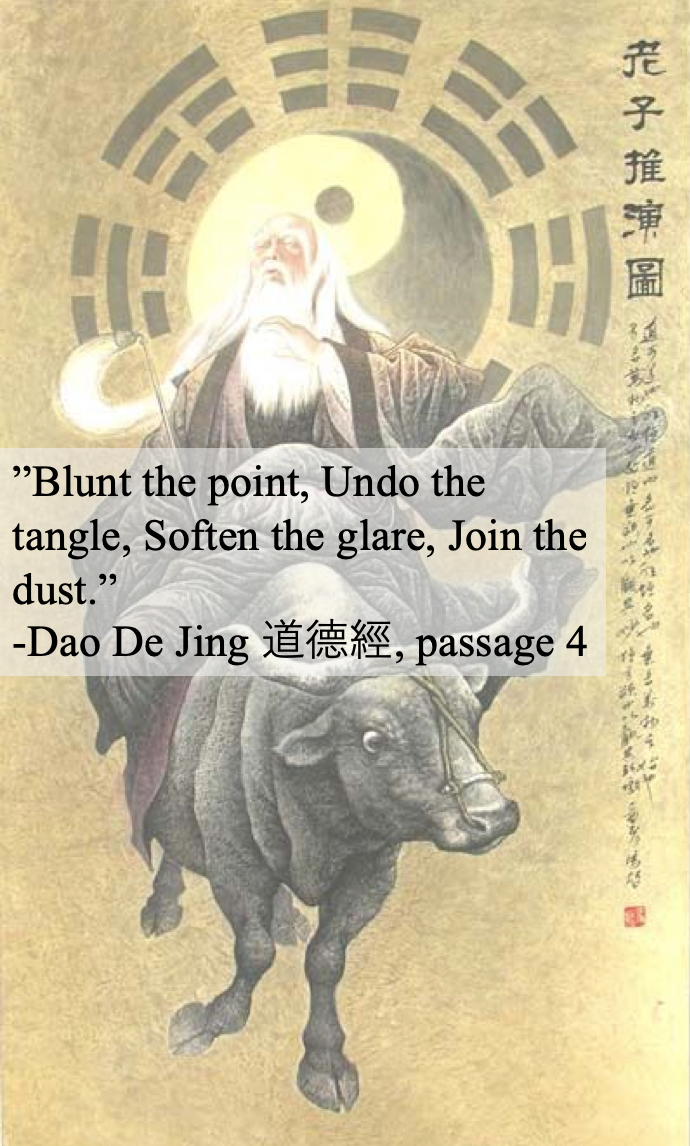

The rhythm of Ding, the cook, is described in the third chapter of the Zhuangzi. To be an expert, as Ding, is to be experienced and natural. This passage of the Zhuangzi reflects the naturalness and ease of Ding’s expertise in undoing the ox.

The rhythmicality is reinforced by the poem’s reference to ‘The Mulberry Forest’, a legendary piece of dance music named after a place called Mulberry Forest in Song territory. In this forest, it is said that the legendary Emperor Tang cut his hair and fingernails short, and offered himself up for sacrifice in exchange for rain to relieve a seven-year drought. The music is used to dance and pray for rain and good crops.

Just like the Mulberry tune, the musicality of the cook’s knife joins life and death as an art. How the ox is cooked and eaten influences affects how the people are nourished, and this ‘how’ is a reflection of the art that synthesizes nature and culture, life and death, and the human and animal (Wu, 1989). All of these things become one another in Ding’s culinary-cosmic dance, where the knife cuts and slithers through the ox and turns it into a feast. Providing such an aesthetic to taking and disassembling life allows the people to feast and be nourished by the animal’s suffering.